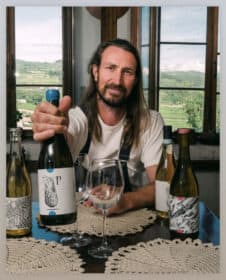

Roterfaden winery

When you think of great German wines, you probably think of the Rieslings from the steep terraces of the Moselle or the Palatinate.

But there is an underdog: the wines from Württemberg. Green Germany, with its rolling hills and many agricultural machines, is traditionally a region with mixed agriculture. Viticulture was almost never the center of a farm, but rather an additional element on the edge.

It was the same with Hannes Hoffman's grandparents. But in Hannes' generation there was a new love for viticulture in the air, which coincided with another love: the meeting with his Greek partner, Οlympia Samara.

Without the parents of winemakers and from a region with no preconceived ideas about what a Württemberg wine should be, the creative minds of Hannes and Olympia were unleashed. Your cellar became a studio for the discovery of Württemberg's potential.

A small excerpt from a conversation with the two of them:

After working with Claus Preisinger in Burgenland, Hannes says:

“We came back fully motivated. Here we have old Lemberger vines, planted in terraced, south-facing vineyards. Everyone says their terroir is unique, but we have this blue limestone that is shaped like slate. We recently discovered that it is very similar to the limestone used by Stéphane Tissot in the Jura. This is something I haven't seen anywhere else with this strain. So we thought the potential must be there? "

The hard blue limestone

In 2014, they returned home and asked if they could take over the half-acre of vines to explore what is possible. In addition to their Lemberger, they also have some Pinot Noir and Riesling. Olympia remembers

“But we really had no idea what potential we had. Nobody worked the way we wanted or made the kind of wines we like to drink. We had nothing to use as a comparison. "

Hannes grins:

“So we started in 2014 with grandpa's tractor. We didn't have a pump in the basement, just buckets. "

From the beginning they worked biodynamically:

“There was never a discussion; we both knew. We had worked in large industrial wineries and in small biodynamic wineries. The latter was just common sense to us, and now we're seeing a little movement in the region. "

Today they also advise other winemakers who want to work biodynamically, although that is not always easy. Olympia notes: "You can quickly see who really wants to work like that and who only does it for marketing reasons."

By hand, they spray sulfur and copper mixed with teas every six to ten days:

“By spraying small amounts frequently, it's like freshening up sunscreen. If it's not there, it won't work. Every week we make about 100 liters of tea, with plants depending on the season - nettle, chamomile, yarrow and sometimes fennel. It also depends on what the garden gives us. And before the harvest, it's horsetail. "

It doesn't stop at biodynamics. Their vineyard practices also fall within the realm of regenerative agriculture. They do not work their floors, nor do they open them. A large mixture of herbs and greens is sown every other row every third year. They let the grasses and flowers grow late into the season to ensure the greatest possible biodiversity. Then, after flowering, they mow the grass with an electric hand lawn mower. It's as environmentally friendly as wine can be.

“Maybe some people think it's a little wild for a vineyard, but it's great for insects. After the first time, we only mow once again - just before the harvest. Otherwise people wouldn't want to come! " Olympia laughs.

The tips of the vines (called the tip) are never cut, but rather rolled under the wire. They also don't make a green harvest (the process of cutting off excess grapes from the vine). Olympia declares

“The vine needs to be given the right information so that it can support and help itself. If you do the green harvest, you are giving the vine wrong information. "

The wines

Your region is severely affected by climate change. Hannes says

“For Germany, it is very warm in Württemberg, and we also have steep, south-facing vineyards. When we were studying in Geisenheim, we probably drank 1,000 liters of Riesling. But the Riesling that we know and love is changing. It is a strain that is not tolerant of drought and heat so we need to think about how to deal with it. She suffers the most. "

Therefore, the first priority in their winemaking is the time of harvest. To make the fresh, crisp wines they love, they have to be on the right side of the acid-sugar balance.

Olympia declares

“We harvest very early. Since we don't have large yields and the weather is so warm it is easy to maintain maturity. The most important thing for us is to maintain the acidity: We believe that this will give us very lively wines with good aging potential and the important factor of drinkability. "

In the cellar people work with their hands and feet.

“Our Riesling is stamped with the foot, with whole grapes. We generally like feet when harvesting, we use our feet a lot. "

The juice and peels then macerate in a cold container for a week before being squeezed in a basket press.

Stamping the Riesling with your feet and slowly pressing it in a basket press ensures that it is saturated with oxygen. While this may seem counter-intuitive when trying to make a fresh wine, it actually works in their favor as it prevents oxidation later on.

“We also prefer the flavors that come from the yeast and ripening. The early addition of oxygen removes these very fruity “primary” flavors. That's fine with us! "

Half of it matures in stainless steel and half in barrels, although they would like to expand the white wine to 100 % in the barrel in the future (like the red wines), as they prefer the barrel aging style. There it matures on the full yeast and is not touched until bottling.

The protocol is always the same for the red wines. You decide on site what percentage of the grapes will remain whole and how much will be destemmed (this depends on the vintage and the quality and taste of the fruit). Olympia declares

"It is actually quite simple. We don't squeeze, pump out, and only use our hands to moisten the surface [known as a lid] once a day. The wine goes into the barrels three to four weeks later. That's it! "

They're picky about their barrels: they have to be older and not have heavy toasted or vanilla aromas.

“New oak would kill the kind of wine we want to make. If you use the right older barrels, the wine is just more alive. The variety is also more evident. Basically, it's just a better wine. After a while you get very picky and sensitive when it comes to barrels. "

It's simple winemaking, but also precise. They add the smallest amount of sulfites to make sure their wines are stable. Hannes says

“We don't like faulty wine. It's not that we are looking for a clean wine, but rather something straightforward and elegant. "

Olympia nods and says

“If a wine has a mouse, then he has a mouse. It's the same with volatile acid or some other fault. I don't care if it's a natural wine or not. "

Hannes and Olympia are first and foremost nature lovers, and the natural beauty of their vineyards can also be found in their bottles. However, this does not happen as if by magic. Rather, it is implemented carefully and meticulously - by hand.

Photos: Roterfaden winery

THEIR WINE

[products ids=”23175,22995,23193,23176″ per_page=”15″ orderby=”menu_order”]